Setup requirements

The degree to which it can be established in how far the test object complies with the requirements determines whether

a test environment is successful. The setup and composition of a test environment therefore depend on the aim of the

test. However, a series of generic requirements with which a test environment must comply to guarantee reliable test

execution can be formulated.

Representative

The test environment must have the properties (as much as possible) that are required for the planned test.

This does not mean that the entire test environment must always equal the production environment. For instance, for a

functional test of an interface between two applications you do not need a complete environment that matches the future

production environment.

Example 1 - For the development of an application intended for

eventual use on a UNIX platform, a Windows-based platform was used as the test environment for the system test. The

assumption was that the functionality would not be affected by the platform difference. A UNIX-based test environment

was used for the UAT and PAT.

Manageable

A manageable environment is required to test the test object under the same conditions every time. It must be clear at

all times which version is installed in a test environment. This applies not only to the test object, but also to all

of the software (i.e. the operating system, database management system, network protocols, etc). Changes in the

components of the test environment (hardware and software, test object, procedures, etc) cannot be implemented unless

with permission from the environment’s owner (in projects, often the test management).

Flexible

A test environment must be easy to adapt. This may conflict with the previous requirement. Which of the

two requirements (manageable or flexible) takes precedence, depends on the aim of the test and the phase of the test

process. For instance, adjustments may be necessary when analysing defects or implementing a new version of the

software. It may also be necessary to create or eliminate specific connections with other systems. If this is done in a

test environment of one project, which has no impact on anybody else, flexibility wins. In case of a shared environment

(e.g. an end-to-end test environment), manageability is preferred. Other examples of possible changes are the system

date and time, currency, calculation units and regional settings. Adjusting the system date and time may be necessary

to make time jumps during testing. This is also called time travelling, making it possible for the system to be moved

to the past or the future. It can be used, for instance, to run a system cycle of one year in just half a day. Changing

regional settings is important when testing software that will be used in several countries.

Continuous

If there are disturbing situations in the test environment, one must try to continue testing as much as

possible. The consequences of a failure must therefore be limited to a minimum. An important mitigating measure is

making regular backups so that they can be restored if necessary. Furthermore, these secured initial situations can be

used time and again for the test or to investigate a specific defect. Another mitigating measure is to create a

fallback option for the test environment. The fallback option may consist of a second logical environment in addition

to the existing test environment. The risk is that, if problems occur in the hardware, they affect both environments.

Another option is therefore to set up a second physical environment. To limit the costs to some extent, the

organisation may decide to combine the second environment with the fallback facility for the production

environment.

Example 2 - When adapting an application that was used for annual contract

renewals, it was necessary to perform tests on several dates and times (time travel). As such, easy modification of the

system date was a requirement for the test environment. Furthermore it was necessary, due to the time travel, to create

regular backups and restore them later. Not a complex combination of operations, but it did put a lot of work pressure

on the administrators of the test environment. It was therefore decided to develop a menu screen containing the various

operations and make it available to the testers. This relieved the administrators and allowed the testers to have

better grip of their environment.

Factors determining the setup

Translating these requirements to the actual setup of a test environment varies for each test. For instance, the test

environment for testing the screens in the system test may be different from that for testing security during the

acceptance test. A large number of factors play a part in setting up the test environment. You will find a list of

determining factors, with a summary explanation, below.

-

The test level for which the environment is intended - unit, system or acceptance test or possibly a combined test.

-

The test type for which the environment is intended - performance, usability, security or regression test?

-

Requirements made by the external organisations for the environment, e.g. supervisors or (local or central)

authorities.

-

Requirements made for the test data to be used. Are they small or big volumes? What is the refresh rate?

-

Existing test environments in the organisation, if any. Can they be used? How can individual requirements be

implemented?

-

Is there a budget for setting up test environments and which options are available?

-

Does the organisation have standards for setting up test environments?

-

The hardware and software architecture. Which development or production platform is being used? What are the

options and which limitations exist, if any?

-

The manner in which system development is organised. The methods, techniques and phasing used for system

development have an impact on the test environments in terms of procedures.

-

The type of system. Clearly the test environment has a strong relationship with the nature of the test object, e.g.

batch, online, mainframe, PC application, custom or package.

-

The level of distributed processing. What extent of data communication exists? And in what form? Is the network or

network programming part of the test object? Are decentralised test sites used? Are there any interfaces with

external organisations?

-

Scope of the test. Should manual processes in e.g. input and output processing be tested as well?

-

The test environments of the programmer and tester must not be too distant in terms of geography. While

communication resources like telephone and e-mail may respond to part of the communication requirement, frequent

consultation between the various stakeholders will be necessary. An optimal location choice can save a lot of time

and money.

-

Sometimes the use of test tools makes demands on the test environment in relation to e.g. security, data storage

and communication resources.

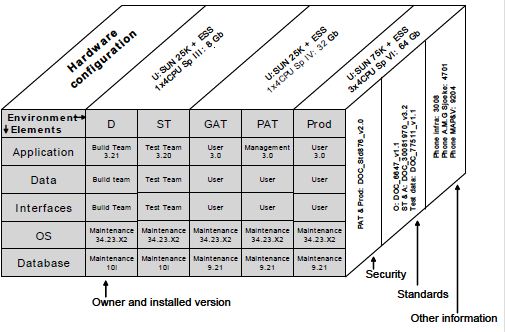

Tips - The cube notation for test environments

A lot of characteristics must be recorded for test environments. Characteristics that are determinants for the

identification of an environment, but also those about which an agreement has to be reached with other parties. The

registration method for these characteristics partly determines the success of the various arrangements. When multiple

test environments are involved, the clear and structured recording of the characteristics may be problematic. One way

to do this is to work with the socalled cube notation. A number of characteristics are placed in each visible plane of

the drawn cube. An example is shown in figure 1 - Cube notation of the various characteristics of a test

environment.

Figure 1 : Cube notation of the various characteristics of a test environment

This makes everything clear at a glance. We recommend hanging this plate in the common test or project space so that

everyone can see the applicable arrangements at any time.

|